So, Just How Bad is This "Administrative Measures for Generative Artificial Intelligence Services (Draft for Solicitation of Comments)"? (Gemini 2.5 Pro Translated Version)

Of course, the heat surrounding this issue has long since passed; after April 11th, discussions even vanished from that certain community where the average user’s annual income is supposedly in the millions. I’m writing this now purely out of the muscle memory of a Ph.D. chasing deadlines, hoping the staff in that office don’t feel I’m adding to their burden.

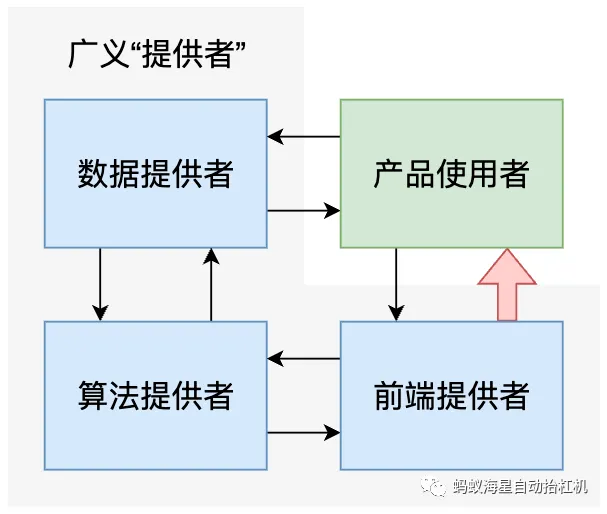

Regarding these administrative measures (this draft for solicitation of comments), criticisms abound, whether from a purely technical or legislative perspective. However, I stand up today to say it is very bad from a metaphysical standpoint, specifically concerning the essential meaning of the “provider” it seeks to regulate. In other words, I believe this draft for solicitation of comments doesn’t even clearly state who the “provider” it intends to manage actually is, yet it directly wields a big stick to manage them. This clearly commits the characteristically Chinese error of focusing on form over substance. Thus, I’ve made a diagram to discuss just what a “provider” is.

Setting aside the more fundamental general infrastructure, and looking only at the chain specialized for “content generation products,” providers can be roughly divided into three modules:

- The module that provides data for the development of generative artificial intelligence.

- The module that utilizes this data to develop generative artificial intelligence.

- The module that utilizes the already developed product to directly provide services to external users.

These three modules can overlap but do not have a subordinate relationship. One module can be operated by multiple entities, and one entity can simultaneously provide multiple modules. For example, a tech startup collects its own data and develops a model, then provides this model as an API to multiple companies/administrative agencies for secondary packaging and use. In this scenario, merely using the term “provider” as described in Article 5 of this draft to regulate this series of behaviors would be rather vague, leading to ultimately unclear rights and responsibilities. The following is a more detailed analysis of this draft for solicitation of comments, based on the interrelationships between the four modules in the diagram:

Data = Algorithm: The relationship between these two is usually quite clear and technical. Data is used to develop algorithms, and algorithms provide feedback on the data based on development results. Articles 7 and 8 in the draft are relevant here, primarily imposing mandatory regulations on the legality of data sources and proposing some “initiatives” (I’m not sure how to accurately describe this) regarding data quality.

Firstly, data quality does not need optimization through administrative management. Whether they are independent data providers or algorithm developers who also handle data, they will be motivated to improve the authenticity, accuracy, etc., of their data. Article 8, in particular, should evaluate fundamental legality or value correctness, rather than the correctness of the content itself.

Secondly, direct responsibility for legality should be reasonably allocated according to the actual data acquisition and usage chain, not just aimed at a broad “provider.” For sources that are not legitimate, or for sources involving users’ personal information, the responsible entities must be clearly identified. For example, if an independent data provider supplies content endangering national security to multiple algorithm developers, only the data provider should be held accountable, not all entities that used this data for development.

Algorithm = Front-end: Although current products from major tech companies tend to present a form where one company handles the entire chain, in reality, it’s still necessary to distinguish whether a broad “provider” has the capability for self-realized algorithms. The draft’s definition of the relationship between these two is currently extremely vague. Relevant articles include 4, 5, 15, and 16.

Article 4 is a very interesting clause, especially its second paragraph. It’s clearly trying to define “provider” through behavior, but from descriptions like “algorithm design,” one can sense that it primarily aims to regulate algorithm providers, defining data and front-end as upstream and downstream behaviors of the algorithm provider. And its fourth paragraph also clearly defines the main responsibility on the algorithm provider, with no additional requirements for separate front-end service providers. This definition will blur the applicability of this mandatory regulation, causing algorithm providers to bear excessive responsibility.

Article 5 follows the general “provider” definition from Article 4 and subsequently points out the possibility that the algorithm provider and the front-end service provider are not the same entity (front-end service provider using programmable interfaces for service). However, in its description, it also tends to identify the algorithm provider as the primary responsible party, without clearly specifying the concrete responsibilities of downstream front-end service providers.

Articles 15 and 16 are essentially a mechanism for front-end providers to give feedback to algorithm providers. Clearly, a front-end service provider that only uses algorithms provided by other entities is incapable of meeting compliance requirements within 3 months. Therefore, the division of responsibilities between the two should be clarified here. Front-end providers should be required to adopt content filtering, while requirements for algorithm optimization should be stipulated separately.

Front-end = User: The relationship between the front-end and the user aligns more closely with the writing tone of most clauses in this draft. Simply put, the front-end provider should be responsible for the content it provides and the user’s usage, and users should have channels to provide feedback on the front-end services they utilize. The main articles involved are 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 17, 18, and 19.

These clauses should clearly not target algorithm providers. Articles 9, 10, and 18, in particular, should have their scope of application specialized to front-end service providers.

Articles related to potential user feedback, such as 11, 12, 13, and 17, should strengthen responsibility to both algorithm and front-end providers.

User = Data: The relationship between users and data providers is more distant, but in reality, data providers might exploit grey areas to collect user usage data and might reward users for actively providing feedback data. The main articles involved here are 7, 11, and 17.

Although Article 7 stipulates protective measures for personal information, the definition of personal information itself should be clarified. While Article 11 provides a partial definition, it is clearly insufficient to fully protect users from personal information security issues encountered during use.

Although Article 17 defines the transparency and disclosure obligations of a broad “provider,” its premise is “upon the request of so-and-so,” and this “so-and-so” should clearly be mentioned in these administrative measures.

Finally, some suggestions to address the ontological definition of “provider”: Firstly, the most reasonable approach would be to clearly define the responsibilities of each module of the provider, targeting the corresponding clauses and penalties to specific entities. A major advantage of this is that it can help unbind responsibility for pure algorithm providers, offering them protection in the field of generative artificial intelligence, which is already in a catch-up state in our country. Secondly, Article 6 could be amended to clarify the general “provider,” for example, by distinguishing between data, algorithm, and front-end “providers” during algorithm filing and managing them separately.

I know you probably don’t like reading this, so you’re welcome to discuss it with me directly. I’ll speak plainly and debate with you.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: