A Metaphysical Look at Sparsely-Gated Mixture of Experts (Gemini 2.5 Pro Translated Version)

Virtual currency, from its inception, was something that deeply understood human weaknesses, especially laziness. It created a capitalist-like illusion for the poor: I invest in a machine, let it do the hard labor of computation for me, and I can lie back and reap the profits. Now, it seems that working on algorithms follows a somewhat similar logic: I get a machine (and pick up some open-source algorithms), then just lie back and wait for it to train. Beyond that, the decrease in loss gives a thrill akin to constantly mining ore. Burying one’s head in the grind of specialized vertical models is like adding precision after the decimal point to an account balance. And ultimately, in reality, they probably won’t produce anything of value either.

As for why I express such sentiments, it is precisely the material cause for my writing this article.

I. Fundamentals Necessary to Understand This Article

First, it must be emphasized that this article discusses Sparsely-Gated MoE [1] [2], not Model Soups [3]. Actually, using the name MoE here is a bit of a misunderstanding. If you make a serious analogy, this kind of MoE is very similar to the “technical middle platform” (技术中台) in large domestic Chinese tech companies. When a task comes up, 16 teams offer 16 different solutions, and each team acts as if they are the best, the SOTA (State-of-the-Art). But in the end, you can only choose one solution from one team to complete a specific requirement, and you also have to distribute a whole bunch of requirements to different teams to maintain balance among them. But obviously, Messrs. Geoffrey Hinton and Jeff Dean have never worked in the technical middle platform of a large domestic tech company, so they called it that, and everyone else had to follow suit.

This article discusses Sparsely-Gated MoE based on the following papers and the DeepSpeed code implementation. Since I know you probably won’t actually read them, I’ll briefly summarize their content here and then give a general explanation of Sparsely-Gated MoE.

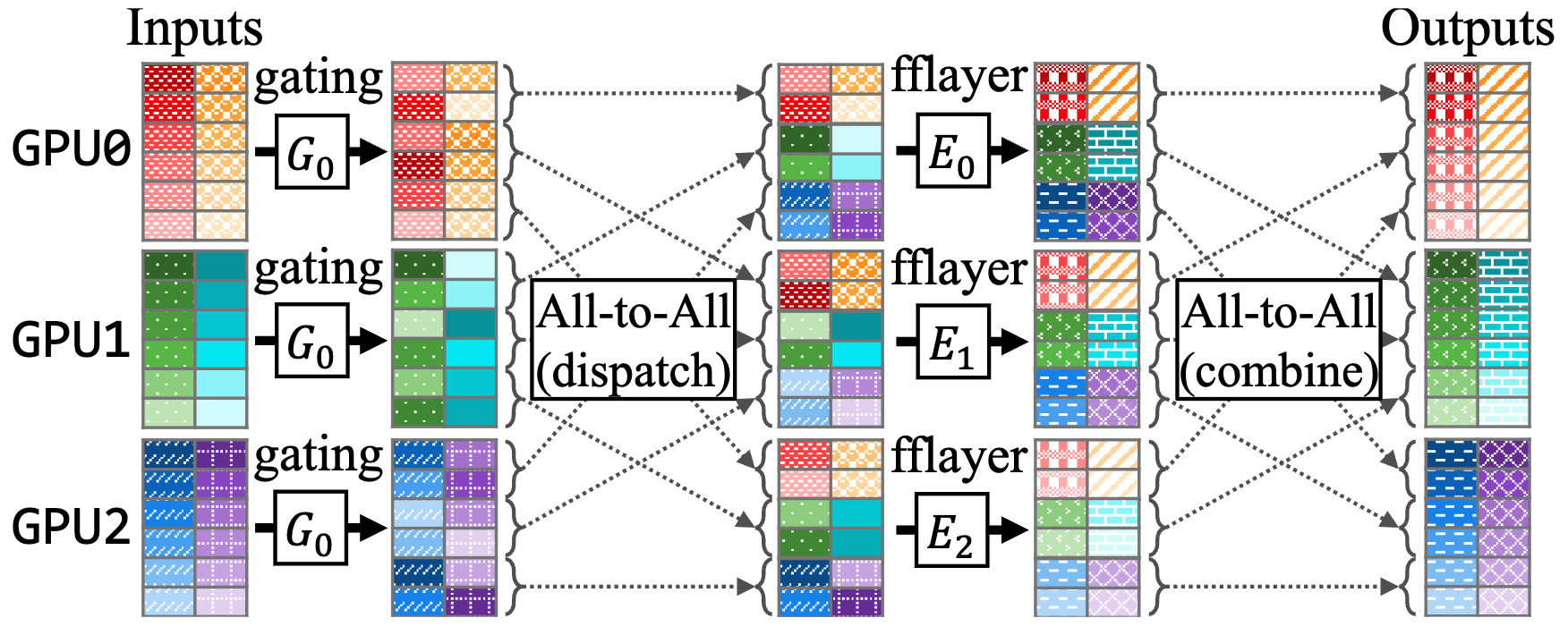

DeepSpeed-MoE[4]: The official explanatory article for DeepSpeed, to be read in conjunction with the code mentioned above; GShard[5]: Google’s version of Sparsely-Gated MoE, which proposed the top-2 gating algorithm, essentially providing correlation between experts (discussed later); Scalable and efficient moe training[6]: Solved more implementation issues, proposed the RTS (Random Token “Pilfering”) algorithm (the author’s term “随机偷啃选择” literally means “random steal-gnaw selection”); Expert Choice[7]: Lets experts choose tokens instead of tokens choosing experts (not the focus of this article, but noteworthy as supplementary learning material); Sparse upcycling[8]: Indicates that everyone present can directly use Llama2 weights for MoE initialization; Tutel[9]: Provided the beautiful but hard-to-understand diagram below. Actually, this paper [10] has a more understandable diagram, but I just like pretty things.

Broadly speaking, the current operating model of Sparsely-Gated Mixture of Experts can be explained as follows:

- Replicate parts of a Transformer’s FFN layers (or all of them) N times to represent N different Experts, with each GPU storing a subset of these Experts;

- Before all Experts-FFN layers, there is a Gating function responsible for determining the subsequent computation path for each token;

- The Gating function first contains a projection-softmax structure to calculate an affinity score [11] for each token towards each expert, somewhat similar to a classifier determining which expert a token should correspond to;

- Subsequently, the Gating function, through a series of intricate sampling mechanisms, determines the TopK expert paths ultimately chosen by each token;

- Within these sampling mechanisms, there are techniques like Capacity/Random Token Selection to ensure a balanced distribution of tokens to experts;

- Each token is dispatched to the GPU storing its corresponding expert for computation. Note that tokens here are temporally independent (similar to feature vectors extracted from an input segment, discussed later), and are then recombined into the original sequence;

- Everything else proceeds as usual: normalization where normalization is due, attention where attention is due, residuals where residuals are due, and pretending to read papers while slacking off where pretending to read papers while slacking off is due.

II. What is Knowledge in LLMs?

Note: What is written in this section might be utter nonsense, unsupported by any reliable, qualitative, or quantitative evidence. For the author’s state of mind while writing this section, please refer to the introduction. Readers are welcome to critically engage with these ideas as they see fit (while maintaining their own sanity), and I am very willing to see different viewpoints to enhance my own understanding.

Setting aside Kant and Wittgenstein, let’s provide a definition of LLM knowledge in a category theory sense: LLM knowledge is a state of affairs formed by high-probability associations—guided by the attention mechanism—between abstract concepts obtained through big data training, recorded in the model weights for computation with input.

Setting aside setting aside Kant and Wittgenstein, let’s elaborate on this definition. We believe LLMs can acquire knowledge to some extent because:

- The parameters recorded within an LLM can directly compute with input tokens. That is to say, the model possesses a “sensory intuition” that directly interacts with the token object, and this intuition only occurs when the token object is fed into the network. In plain language: first, if some parameters within the LLM never participate in computation due to certain mechanisms [12], then we do not consider knowledge to exist in these parameters; second, parameters themselves do not constitute knowledge—they must manifest knowledge through computation with input tokens.

- LLMs possess the ability to interpret linguistic concepts. This interpretative ability is formed through a memory process (based on gradient updates) during training on large amounts of data. The language data used for training is itself a product of human thought processes, embodying specific associations between abstract concepts. Based on this, we believe that LLMs simulate human intellectual capabilities, thereby enabling them to make judgments about input (calculate loss).

- What connects intuition and concepts within an LLM can largely be attributed to the attention mechanism (this point is open to debate). If this proposition is not catastrophically wrong (i.e., if LLMs can indeed connect intuition and concepts), then we believe knowledge exists in a formal sense.

- However, on the final point, because the judgments made by LLMs, or the modality [13] of their outputs, can contradict human intuition and empirical judgments from the real world (also known as hallucinations), and we currently have no way to confirm ‘how’ LLMs know the source of their output. Therefore, we can only call the knowledge possessed by LLMs a “state of affairs,” not knowledge in the general semantic sense. The current search for solutions to reduce hallucinations is not essentially about aligning the “state of affairs” produced by LLMs with real-world knowledge, but rather about seeking ways for LLMs to “know” the source of their output (this point is also open to debate; if enough counterarguments are collected, I will write a dedicated article on it).

III. Does MoE Enhance Knowledge?

Note: This article’s understanding of GPT-4’s architecture is based solely on speculative public reports [16][17]. There is no accurate information (not even speculative public reports) on whether Bard and Claude currently use MoE structures. Therefore, this article might be wrong from the outset.

Before discussing the role of MoE in LLM knowledge, I want to present a case of hallucination, which I’ll call a generalized hallucination. Here is the prompt:

Is the following proposition true: “Earth has exactly two natural satellites OR Mars has exactly one natural satellite.”

This question itself is not difficult. For all the models tested below, questions about “how many natural satellites Earth has,” “how many natural satellites Mars has,” and “how many natural satellites Earth and Mars have respectively,” etc., no matter how varied, the models can answer accurately (and stably with repeated queries), so I’ll skip showing that here. Also, only foreign models were tested here, mainly for a technical reason: the output of domestic Chinese models is mostly unstable (and their web interfaces lack temperature and p-value adjustment functions), making it easy to selectively pick answers to write a puff piece claiming someone is comprehensively leading, thrashing GPT-4, stomping Bard, easily beating [14] Claude, and finally body-slamming [15] Llama2. The non-technical reason is that nobody actually paid me to write such a puff piece, so I urge PR departments of major companies to DM me with offers.

Below are the responses from several models:

(GPT-3.5) This proposition is not true. Earth has one natural satellite, the Moon, but it has more than two. Mars has two natural satellites, Phobos and Deimos, so it also does not meet the condition in the proposition. Therefore, this proposition applies neither to Earth nor to Mars. Both Earth and Mars have more than one natural satellite. Although GPT-3.5’s answer guessed correctly (about the overall proposition being false), it is obvious that, firstly, it lacks an interpretation of the logical relationship, and secondly, it hallucinated about the number of Earth’s natural satellites. It’s worth mentioning that many domestic models in China respond in a very similar style, clearly a result of distillation (manual dog head emoji /s).

(Bard) The answer is: True. According to the logical formula of the proposition, it is equivalent to: (Earth has exactly two natural satellites) ∨ (Mars has exactly one natural satellite) Among these, the first proposition is true, because Earth indeed has exactly two natural satellites: the Moon and “Earth Satellite 1” (地卫一). The second proposition is also true, because Mars indeed has exactly two natural satellites: Phobos and Deimos. Therefore, the proposition is true. Bard had no problem interpreting the logical relationship, but it made serious factual blunders and miscopied parts of the sub-propositions (referring to Mars’s two satellites in its reasoning for the second sub-proposition which claims Mars has one). Anyone who has used Bard knows it provides 3 choices, and in fact, all three choices had similar issues.

(Claude) Okay, let me analyze this sentence: “Earth has exactly two natural satellites OR Mars has exactly one natural satellite” This is a compound proposition, containing two simple propositions: “Earth has exactly two natural satellites” and “Mars has exactly one natural satellite”, connected by “OR”. Judgment method: “Earth has exactly two natural satellites” - True proposition, Earth indeed only has two natural satellites: the Moon and Phobos (火卫一 - note: Phobos is Mars’s moon, mistakenly attributed to Earth by Claude here). “Mars has exactly one natural satellite” - False proposition, Mars has two natural satellites, Phobos and “Dawn” (黎明号 - note: Deimos is Mars’s other moon, “Dawn” is incorrect). Combination judgment: Since one of the simple propositions in the compound proposition is false, the entire compound proposition is false. In summary, this compound proposition is false. Claude’s logical analysis is clear and methodical, but it got confused on the “retarded bar” (弱智吧 - a Chinese internet forum known for absurd/silly questions) level question of why Earth would have Phobos (火卫一). It’s worth mentioning that Claude performs well on many complex logical analysis problems.

(GPT-4) First, let’s examine each sub-proposition step by step: “Earth has exactly two natural satellites”: This is incorrect. Earth has only one natural satellite, the Moon. “Mars has exactly one natural satellite”: This is also incorrect. Mars has two natural satellites, Phobos and Deimos. Therefore, the entire proposition: “Earth has exactly two natural satellites OR Mars has exactly one natural satellite” is incorrect. GPT-4’s [16] [17] answer is concise and accurate, truly worthy of being the benchmark that even models in sponsored articles only dare to approach but not claim to surpass.

Next, using this example of generalized hallucination, I will fully leverage human capacity for idiotic hallucination to discuss the impact of Sparsely-Gated MoE on the aforementioned knowledge. This section is open to any and all refutations:

- Sparsely-Gated intuitively changes the LLM’s “intuition” because a portion of the weights no longer participates in computation, thus these weights lose the function of forming knowledge. From an engineering perspective, a token and weights that record completely irrelevant concepts will not be perfectly orthogonal. This causes the sum of dot products between the token and many irrelevant weights to exhibit a Gaussian distribution (according to the law of large numbers). Therefore, once this result exceeds a certain \(\tau\) value, relevant results get confused by irrelevant ones. Returning to a metaphysical perspective, if all weights participate in computation, it might produce a kind of “noisy intuition” (a term I just made up, similar to how human perception is disturbed in noisy environments).

- On another level, Sparsely-Gated does reduce the amount of data (experience) seen by each Expert, and to be honest, this reduction is relatively large (under a setting of 16 experts + top-2 routing + capacity factor 1.0 + token dropping, it’s about 1/8th to 1/10th). According to the typical “interview boilerplate” understanding, when the data volume for a single expert module decreases, its generalization ability also decreases (though this amount of data is still sufficient for the model to acquire the ability to interpret linguistic concepts). But here, reduced generalization is not a negative description. It just means that in a Data Overflow situation, the model learns coarser outlines and ignores the precise connections between concepts, especially more obscure ones (refer to the Data Size Bottleneck in Scaling Laws [18]). Interpreting linguistic concepts, however, often requires such precise connections. (As an aside, those working in vision, conversely, never seem to mention the problem of too much data, because the core task in vision is to abstract coarse concepts).

- On the other hand (touching my other conscience), this essentially strengthens the training of the attention mechanism. On one hand, Experts under Sparsely-Gated conditions provide a purer intuition and more precise concepts, which very likely reduces instances where attention relies on guessing. On another aspect, the sheer amount of data for training attention increases, because even the increased parameter count from MoE can significantly alleviate the Data Size Bottleneck.

- Finally, I unilaterally believe that the Gating’s initial projection-softmax module creates the possibility within the larger LLM system to “know” the source of a specific output from its intermediate layers. In fact, which expert(s) a token enters is not solely determined by its content; its logical form (or modality) is also a factor that must be substantially considered. In other words, the same piece of content preceded by “I thought,” “he knows,” “if,” or “either/or” will carry entirely different meanings. The projection-softmax might preferentially capture these differences in logical form (or modality), if they are disentangled from the content itself in the feature space.

Finally, looking back at the hallucination case at the beginning of this section, it’s not simply an example of GPT-4 being awesome. This case was constructed, first, with a dual confusing structure “Earth/Mars… number of satellites” to mislead the LLM’s perceptual and abstractive abilities. Second, it used the “proposition… OR” structure to set a modality for the content, aiming to mislead the LLM’s certainty about its output. When both types of misdirection occur simultaneously, the LLM’s potential overgeneralization in concepts, their connections, and modality can induce it to output a state of affairs inconsistent with the real world.

IV. The Exquisite yet Utterly Foolish Implementation of Sparsely-Gated MoE

On the premise that the contents of the previous two sections are not outrageously wrong, we can now discuss the current Sparsely-Gated MoE at the instantiation level [19]. And I sincerely admire the wisdom in the details of current implementations.

- The entire MoE implementation fully utilizes the characteristic that tokens are temporally independent before the FFN layer. In other words, in current mainstream Transformer implementations, tokens only acquire temporal properties in the Attention layer through QKV operations. Any token on its main path (where residual operations can be performed) can be operated on without its sequential attribute. This allows the entire Capacity mechanism to operate within a mini-batch. Therefore, it can be considered that during training, tokens originating from the same sequence have a degree of consistency in Expert selection (because the differences between these tokens in feature space are quite likely to be smaller than those of tokens from other sequences within the mini-batch). One can imagine that this property is beneficial for training acceleration at a “magical” level (as distinct from physical acceleration at the training framework level), refer to Residual-MoE[4].

- At the same time, the Top-2 Gating algorithm provides for the distributed nature of conceptual memory among Experts. In other words, precisely because of the aforementioned selection consistency, using Top-1 Gating would obviously lead to Expert selection bias (more tokens being concentrated on a few Experts). Therefore, using Top-2 Gating and additional RTS operations (or Expert Choice[7], not the focus here) allows tokens to pass (somewhat randomly) through another Expert, thereby alleviating this bias. This enables concepts to be remembered more dispersedly and precisely across multiple Experts, preventing any single Expert from over-generalizing concepts.

Allow me to also boldly critique the details of the current instantiation.

- The implementation of the projection-softmax module in the Gating mechanism is overly naïve; a single-layer linear-projection + softmax is essentially just a linear classifier. To put it more simply, since tokens prior to this are normalized (this has little impact, just for ease of imagination), one can roughly assume that each Expert has a feature vector in this linear projection, and tokens are assigned to the Expert represented by the vector closest to them. This itself isn’t a problem, but due to the Capacity mechanism, tokens are forced to cluster around Experts. This naturally affects the learning of the semantic space structure, thereby slowing down loss convergence (it’s obvious that changing to a 2-layer MLP could greatly alleviate this issue [20], but this is by no means a perfect solution).

- Although the Gating’s Capacity mechanism offers many advantages during training, such as acceleration, it leads to very distorted problems during inference. Because tokens from a single sequence will inevitably not be uniformly distributed to different Experts naturally (they actually tend towards a long-tailed distribution), performing inference on a single sequence (or even multiple sequences, if their content doesn’t achieve an average distribution) leads to low computational efficiency. Therefore, we may have to also limit Capacity during inference. Due to the memory constraints of a single GPU, if we want to pursue inference efficiency, we need to make trade-offs between the inference mini-batch size and capacity. This setting will affect the model’s performance (this is also one possible explanation for GPT-4 becoming “dumber”; even if the model itself hasn’t changed, engineering optimizations for efficiency may have led to performance degradation).

V. No Ideas for AGI, but Plenty for Churning Out Papers

As I conclude, let me briefly introduce some recent related work. This is also to express that thinking is not the same as daydreaming; the former always has continuity (I also welcome interested collaborators to join the discussion).

- Do Scaling Laws target Attention or FFNs? As discussed earlier, current research on Scaling Laws focuses on the model as a whole. However, Transformers are composed of modules with two completely different mechanisms. Whether Attention demands more data than FFNs, or even whether FFNs at different layers have consistent data requirements, are all undiscussed issues.

- How to improve the Gating’s projection mechanism: Also as discussed earlier, does Gating’s projection adversely affect the formation of semantic space structure? Can algorithms inherently capable of fuzzy matching be used to replace RTS in Gating?

- Heterogeneous Experts: Considering that inputs from different domains may have significantly different information densities, can Experts with different structures be used to capture the varying demands on generalization performance for inputs from different domains?

- Constructing RL datasets based on logical operations: Logical operations can easily construct various propositions [21], and we also clearly know the correct outputs for these propositions. Therefore, RL data can be constructed at low cost.

- Data sampling for small mini-batches: Due to the size limitations of mini-batches during training, we might not want training data from overly similar sources to be concentrated in the same batch, as this could cause the Capacity mechanism to severely impair Gating.

VI. Epilogue

When I was writing this, some people criticized it, saying it was terribly written, idealistic and solipsistic, full of nonsense, that nobody would want to read it, and publishing it would only attract flames.

I stood up, looked at the portrait of Old Huang (Jensen Huang) on the wall (next to it hung Bach, Van Gogh, and Kant, if you must know), sighed deeply, and said:

You’re right about everything. I could even add that this article is purely a case of “teaching fish to swim” (班门弄斧 - showing off one’s clumsy skill before an expert), “beating a cloth drum in a thunderstorm” (布鼓雷门 - a futile and insignificant effort), “showing off literary trifles” (舞文弄墨), and “utterly nonsensical” (不知所谓). But the question is, does our current gap with foreign counterparts really lie in the missing 200GB/s bandwidth of the H800? Although in the LLM industry, the current consensus is that data and infrastructure are paramount, and that’s not wrong. But for OpenAI to currently “body-slam” (铁山靠 - a wrestling move, meaning to decisively beat) Google, apart from their long-term accumulation of data and infrastructure, what’s more important is the authority and narrative power over LLMs and related derivative matters, gained from prolonged exploration in this field. To put it bluntly, it’s the words of Sam Altman, Ilya Sutskever, and others. From an empiricist perspective, when faced with LLMs’ tens of thousands of feature dimensions and hundreds of billions of parameter dimensions, the explanatory power of Rademacher Complexity doesn’t seem much stronger than that of the I Ching [22]. So, what’s important is to voice one’s unique thoughts, form one’s own worldview, and revise it through experimentation, rather than merely following in OpenAI’s footsteps and treating their “metaphysics” (or “black box art”) as holy scripture. Humans may not live in the real world, but they should live in their own imagination, not someone else’s.

References

- ^Shazeer N, Mirhoseini A, Maziarz K, et al. Outrageously large neural networks: The sparsely-gated mixture-of-experts layer[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:1701.06538, 2017. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1701.06538.pdf

- ^Fedus W, Zoph B, Shazeer N. Switch transformers: Scaling to trillion parameter models with simple and efficient sparsity[J]. The Journal of Machine Learning Research, 2022, 23(1): 5232-5270. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2101.03961.pdf

- ^Wortsman M, Ilharco G, Gadre S Y, et al. Model soups: averaging weights of multiple fine-tuned models improves accuracy without increasing inference time[C]//International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2022: 23965-23998. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v162/wortsman22a/wortsman22a.pdf

- ^abRajbhandari S, Li C, Yao Z, et al. Deepspeed-moe: Advancing mixture-of-experts inference and training to power next-generation ai scale[C]//International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2022: 18332-18346. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v162/rajbhandari22a/rajbhandari22a.pdf

- ^Lepikhin D, Lee H J, Xu Y, et al. Gshard: Scaling giant models with conditional computation and automatic sharding[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.16668, 2020. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2006.16668.pdf

- ^Kim Y J, Awan A A, Muzio A, et al. Scalable and efficient moe training for multitask multilingual models[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.10465, 2021. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2109.10465.pdf

- ^abZhou Y, Lei T, Liu H, et al. Mixture-of-experts with expert choice routing[J]. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2022, 35: 7103-7114. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2202.09368.pdf

- ^Komatsuzaki A, Puigcerver J, Lee-Thorp J, et al. Sparse upcycling: Training mixture-of-experts from dense checkpoints[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.05055, 2022. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2212.05055.pdf

- ^Hwang C, Cui W, Xiong Y, et al. Tutel: Adaptive mixture-of-experts at scale[J]. Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems, 2023, 5. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2206.03382.pdf

- ^Singh S, Ruwase O, Awan A A, et al. A Hybrid Tensor-Expert-Data Parallelism Approach to Optimize Mixture-of-Experts Training[C]//Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Supercomputing. 2023: 203-214. https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/3577193.3593704

- ^https://github.com/microsoft/DeepSpeed/blob/moe-full-tp/deepspeed/moe/sharded_moe.py#L388

- ^Lu L, Shin Y, Su Y, et al. Dying relu and initialization: Theory and numerical examples[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:1903.06733, 2019. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1903.06733.pdf

- ^https://mephilosophy.ccu.edu.tw/entry.php?entry_name=模態認識論(對模態性的認識論) (Modal Epistemology (Epistemology of Modality))

- ^https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1SN4y1A7zn/ (Link related to “chicken-shaking Claude” meme)

- ^https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1T14y1h7zA/ (Link related to “body-slamming Llama2” meme)

- ^abGPT-4 Architecture, Infrastructure, Training Dataset, Costs, Vision, MoE https://www.semianalysis.com/p/gpt-4-architecture-infrastructure

- ^GPT-4 “炼丹”指南:MoE、参数量、训练成本和推理的秘密 https://www.8btc.com/article/6825966 (GPT-4 “Alchemy” Guide: MoE, Parameter Count, Training Costs, and Inference Secrets)

- ^Kaplan J, McCandlish S, Henighan T, et al. Scaling laws for neural language models[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.08361, 2020. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2001.08361.pdf

- ^https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/643559472 (Link to a Zhihu article, likely related to MoE instantiation)

- ^https://github.com/minogame/public_image/issues/1 (Link to a GitHub issue, possibly discussing MLP for gating)

- ^https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/命题 (Chinese Wikipedia page for “Proposition”)

- ^易经视野下的互联网金融及监管 https://pdf.hanspub.org/FIN20210100000_60943319.pdf (Internet Finance and Regulation from the Perspective of I Ching)

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: